陆亮作品-网站

LU LIANG

陆亮作品-网站

LU LIANG

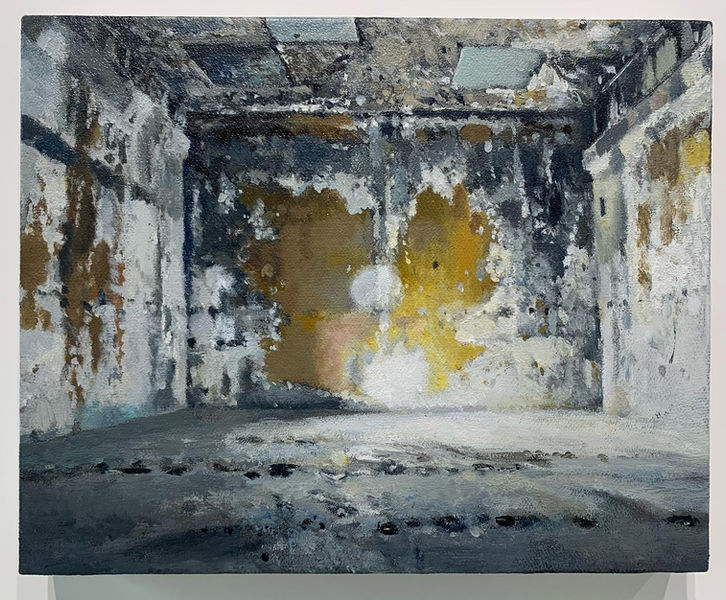

魔窟

2015

夜路加字幕

2014

Texts

Li Xu

Director of Z-Art Center, Shanghai

It has already been ten years since I met Lu Liang for the first time.

Then he was still studying in the mural painting department in Central academy of Fine Arts, and showed me the photos of his exercise works of sketch and oil painting when he visited his family in Shanghai during the summer vacation. I only felt that he was a very diligent student with good foundation of plastic art, though his creation hadn’t started yet. He didn’t choose the smart and ingratiating style, which was concerned with his steady and conscientious personality. Well-disciplined brushwork of classic academicism is low-yielding and quite difficult, and it really needs inexorable perseverance to form individuality in this.

Ten years later, when I saw Lu Liang again, he had gradated as a MA from the academy and taught there. Influenced by his tutors Chen Wenji and Cao Li, his individual style has initially formed, and the series of works after 2004 is unexpectedly refreshing.

Without any sense of gaudiness or extravagance, Lu’s works are obviously opposite to the classic style popular in the art market. Almost all the models under his paintbrush are male, mostly the peasant workers common in life. The paintings are generally shrouded in the solemnity of dark hue, depicting the traditional Chinese fables unfamiliar to the contemporary people, and prevailing with the atmosphere of philosophic speculation. From the perspective of painting language, Lu directly benefits from the western classic masters, such as Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Latour, and etc, however, he narrates extremely personal stories in such a language. Living in Beijing for a long time makes him suspicious and worried about the vicissitudes of contemporary metropolises. He always sighs and mediates about the endless expansion of city’s scale, pollution and damage of ecological environment and the disseverment and separation in historical memory. The creation of series on the themes of fable, legend and fantasy expresses his meditation on these solemn topics in the way of surrealism.

Besides the figure, another important theme of Lu’s works is landscape. Without daylight, these landscapes only have night, dawn and twilight. Like those figure paintings, all the scenes are unfolded under various lights: the unclear sun, dim fluorescent light, shocking lightning, aggressive flashlight, and etc. As the absolute leading character hidden in Lu’s works, the light traverses air and floating dust and integrates with shade and color. Eventually, all the scenes are reflected on our retinae in the form of light. Influenced by Gerhard Richter, a

German master, many domestic artists who create with the help of photography would usually emphasize the tendency of flatness, lightness and void, while Lu is quite different. To precisely depict the subtle reflection of light on different objects and numerous details of sense of reality, he often re-operates on his works again and again, and the process of depiction, polish and re-depiction would repeat for seven or eight times, sometimes even ten times. Therefore, no print would ever realistically reproduce the actual effect of these works, which is

apparently a great pity for the audience unable to see the originals. It may be said that, Lu is a perseverant artist insisting on depicting the light, and his name Liang means light, which is probably not a mere coincidence.

In the times when various international exhibitions are filled with the forms of multi-media, painting has been quietly returning. In the circle of Chinese contemporary art, the trend of conceptual painting is gradually flourishing. Could the skill of classic painting revive in the current times? Could the concept of realism generate a whole-new significance? I believe, Lu Liang’s continuous efforts would surely present an answer with extreme individual charm for us.

November 15, 2007

Song Xiaoxia

A dense cloud of smog hangs over the city of Beijing without being dissipated for days on end, obscuring all the ancient and modern landmarks of the metropolis; the Ten Great Buildings in the walled inner city, the CCTV building on East Third Ring Road and the Pangu Plaza on North Fourth Ring Road are all secreted by the smoke. A wisecrack on the internet says that this is so because Beijing had become the mythical, fog-encircled land of the saints and immortals. But the reports and analyses of PM2.5 particles on the news evoke a sense of unease, anxiety and helplessness; we feel deprived of air, as if we fear to breath. This omnipresent and inexplicable stimulus induces a hopelessness that is beyond escape. In the smog, there is people, a city and many breathings; there is also sudden death, accompanied by a relentless spiritual apprehension that finally leads to despair. Lu Liang’s artwork situates this spiritual apprehension he calls “the mien of contemporary Chinese society” in the most commonplace of scenes.

Ruins in the night; a pile of broken-up bricks; a burning garbage heap; an abandoned movie theater; a coal storage with no stores left; a quarantined sickroom; a gloomy tunnel; a line of willow trees by the side of the road at night; a rain-flooded underground passage from which rain water had just been drained; a blank steel billboard under the twilight – Lu Liang’s paintings feature the gradual erasure of people as well as the narrative in their imagery. What remains on canvas are the scenes themselves, benighted and dismal, such as a concrete floor illuminated by electric lights; a patch of dirt and tire tracks in the mud, and they forcefully take hold of us. Lu Liang said, “Abruptly extricate objects from everyday life, severe them from their environs and give them a beam of light – at that instant they acquire meaning.” Lu Liang’s paintings shed light to the microscopic fissures of our perception, which conceals the experience of everyday life, suddenly exposing them to the light of day.

Lu Liang’s relationship with objective reality is predominantly emotive. When Lu painted willow trees, he waited two years for the perfect moment to capture willow leaves covered in dust. That moment allowed Lu’s art to break through the murkiness of objective reality, the opacity of memory, and layers upon layers of historical and cultural heritage. The odor of rubbish heap that lingered in his studio, and that of fiberglass from the sculpture studio next doors, also comes through to the viewer. In modern life that is rife with rapid change, Lu Liang deliberately opens up his sensibilities to this world without hurry. He reads, he pays rapt attention to the issues, but he does not allow intellectual concepts or concerns to dictate what he paints. Rather than the product of reasoned analysis, Lu Liang’s works are the direct output of his lived experience; they come from his incisive and deeply felt emotions. The dusty corners of everyday life that he excavates through his paintings have the power to tend our own times to the quick.

Lu Liang prefers the rich colors of deep night. What does he see in the dim, murky lights of the night in his wanderings? An “invisible hand” seems to haunt the darkness. Just what is broken in Brick Pile? And what is incinerated by Burning? Coal Storage is a milestone of a masterpiece among Lu Liang’s works. Emblematic of Lu Liang’s ability to express utter dread with utter calm, every inch of the canvas exudes a disquiet that is more horrifying than any intellectual discourse on energy supplies, human survival or environmental preservation. If Nanhu Cinema is the last, loving backward glance to the society that we left behind, Night Road – Safety Passageway is a horrific look at our society in the present. On Night Road – Willow, the artist remarks: “It was a forlorn road in an oppressive night, at the end of which there is only suffocating darkness. It was nightmarishly alone and crawling with danger.” The dark atmosphere in those scenes of the night is but the emissions of our own lived reality. For Lu Liang, the true picture of our times is best captured not by depicting its people, but by painting its nightscapes.

From a worldwide perspective, Lu Liang’s current artworks are excellent. He has his own opinions and character, as well as unique substance and a distinct style. Lu’s ambition to create “a portrait of the times” is shared by many contemporary Chinese artists. What is unique to Lu Liang is the realization of that ambition on canvas, its concrete visual expression. We do not need to go into lengthy discussion of the long history of European classical oil painting that sought to translate the artist’s apprehension of the world and perception of “reality” with oils on canvas, nor do we need to narrate the numerous shifts and changes that took place in Chinese art since the adoption of the realistic oil painting over a hundred years ago. There are fall traps enough in the artistic and stylistic conflict between the ancient and the modern, the oriental and occidental, and the siren song of the marketplace. Lu Liang does it the hard way; in his words I have heard years ago, “Happiness is to find an image that one can work real effort into its painting.”

Contemporary art is inclined away from visualization, but Lu Liang goes against the grain. He wants to “work real effort” into the images, to repeatedly use “torturous” strokes to reveal and express the subtle emotions and finer sensibilities that images possess in themselves but photography cannot capture. Like a farmer tilling his field, Lu digs into the images that he paints, and in his unique style he reconstructs the “connectivity” between image and emotion. In Nanhu Cinema, Lu painstakingly worked and reworked his rendering of the concrete floor, crafting the green sheen of old fashioned concrete that had been stamped by countless feet. The jade-like hue and texture establish a “connectivity” with our conflicted feelings toward a vanishing way of life. The many blurry and crisp visual details of Night Road – Safety Passageway, including the long scratch marks on the top of the tunnel, the muddy tire tracks, the water-soaked electrical wires and the ghost fire lights of the buildings in the distance have all been worked on by Lu Liang’s art into a powerful “connectivity” with our own apprehension and anxiety. The willow trees of Night Road – Willow are covered in dust – perhaps from a construction site nearby – the pebbles and grains of dirt on the ground are fashioned into a “connectivity” to our fears about the environment. Even the leaves on Lu Liang’s willow trees appear dried up and infected, like a rash that afflicts a corner of the mouth that elicits pain from every movement.

Though the scenes of Lu Liang’s paintings are drawn from neglected corners of everyday life, the inspiration of Brick Pile comes from the shipwreck and icebergs in the seascapes by Casper David Friedrich. In the manner of a poet working classical references into his own poetry, Lu’s works often allude to western classical painting. Intriguingly, Lu Liang sees a mysterious and ineffable cosmic force in the life-like style of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Manet and Goya. Lu Liang integrated the visual experience of classical painting with the context of contemporary painting and formed his own aesthetics of the world. The result is the fashioning of a creative continuity with the classical past in modern China.

Lu’s Dreaming of the Tiger Spring is a courageous conversation with the Chinese classical art: a shining mountain stands in the complex shapes and colors of his oil composition, at once solidly sustentative and illusory, as in a mirage. To endow the mountain rocks with movement and a sense of wetness and solidity, Lu Liang’s palette has the light touch of an ancient fresco, while his strokes evoke the rich thickness of Fan Kuan and Huang Binhong. In Coal Storage, the shape of the coal piles and the brushstrokes on the canvas appears to pay homage to the composition and brushstroke style in the landscapes of Dong Yuan, Mi Fu, Mi Youren and Gao Kegong. The composition of the willows in Night Road – Willow is reminiscent of imagery of The Classics of Poetry: “As I journeyed away, / I saw the drifting of the willow trees”, and the classical landscape paintings from the Song Dynasty. Of course, Lu Liang expresses all this in the composition of western oil painting; in his opaque way, Lu seeks to plant the classical forms deeply and solidly into his oil soil.

Lu’s painting is an ever-more time-consuming process; completing a painting takes anywhere from a couple of months to several years of labor. Some may say that nowhere in the world can one find a place as complicated and absurd as modern China. Lu Liang’s paintings are not profound because they are profound portrayals of reality; rather, they are profound because the artist’s emotive apprehension of reality is profound. When confronted by Lu Liang’s paintings, one can almost hear them giving deep sighs. Lu has created the imagery of the contemporary age in an unprecedented way. They are of the neglected corners of everyday life, imbued with overpowering spiritual apprehension; the silent images that, in its darkness, give rise to insuppressible drives and impulses. Lu’s paintings contain both the spark of life within and a surprising spirit of scrutiny and criticism from without.

Lu Liang is the lyric poet of our times; his paintings are the real landmarks of this age.

Chen Wenji

Some people paint to achieve success; some, however, paint out of dissatisfaction.

Those who are hindered by the particular circumstances of their artistic maturation and the lack of support from their communities often fail to achieve in their adult lives the desired integration into society. They attemp at breaking through but are met with frustration time and again, leaving them in a state of doubt and anxiety. The psychological impact turns their gaze inward and drives them into exercising extraordinary care in their day-to-day lives; constant use of caution wears their nerves to hypersensitivity, but also sharpens their faculties. Their approach to art is often anxious and humble; inadvertently, those are the very qualities that make an artist excel. I call those artists who paint out of dissatisfaction.

I would speculate, based on the hint of introspective repression that I can always detect when examining Lu’s work, that he is one of those who paint out of dissatisfaction. For him, painting is a laborious and painstaking process of constant revisions and improvements. Lu does not shy away from making major changes even at the final stages of working on a painting, and often inspite of the fact that he was fully committed to a different vision initially. This gives his works the enduring quality of being able to withstand careful scrutiny; when considered as a whole, one can readily appreciate the absence of the over-polishedness of mass-produced paintings.

To others, Lu’s life appeared to be that of smooth sailing; he entered the Central Academy of Fine Arts in the nineties, advancing from undergraduate to graduate to professoriate without complications. One of his student sketches won an annual award from the Academy. He was a model student; on the surface, he was no different from other artists of his time.

But the early blooming of dissatisfaction he felt inside prevented Lu from attaining the ease and comfort he seemed destined for. Lu was deeply engaged in contemporary artistic trends even when he was a student, and therefore developed a hefty skepticism towards the conventional approach of his academic education, at which he balked. He privately experimented with numerous mediums and styles, but did not find a clear direction for a long time. Lu Liang definitively established the realistic style he is now renowned for a decade ago in his late twenties. In a series of sketches and studies in oils, Lu gradually laid claim to a path of his own, choosing to paint in a realistic manner reminiscent of the Neoclassical tradition as the sole means of expressing his artistic identity during that period. It was a shocking choice that went completely against the grain of his contemporaries. His self-imposed marginalization was a melancholic yet powerful gesture.

Entering the domain of realistic painting, Lu Liang could easily have found commercial success with his thoroughly practiced skill at painting from life — had he followed the well-tread path of his predecessors. But Lu’s passion for themes and aesthetics that are considered by most to be visually difficult and challenging denied him easy success. To define his own approach to art, Lu Liang adopted a unique style that I call “bitter, hard-edged aesthetics”. Here is a man who is constantly struggling with himself in elaborating his philosophy of art, as well as in setting his own standards of beauty. Every painstaking stroke of his painting reveals constant, unresolved conflict within his own artistic program and skepticism of the subject being depicted. It can be said, therefore, that Lu’s unique artistic spirit is forged in the crucible of his self-doubt. The fable-like themes of his early paintings are enigmatic visual texts, while his backdrops of the twilight and the night time blazes, so evocative of loneliness and despair, are often disturbing to the viewer. In recent years, Lu is interested in depicting scenes from everyday life with emotionless precision — beneath the surface of which lay an inexplicable melancholy and helplessness. His later works also convey a sense of dread by freezing the passage of time, and are pervaded by an unsettling feeling that the accustomed conventions of order and beauty had been disturbed. In their stead, Lu puts his stamp on an aesthetic that is distinctly and uniquely his own.

Today, Lu Liang’s refusal to adopt an ingratiating style is recognized as noble. He says: “Happiness is to find an image that one can work real effort into its painting.” The fruits of Lu Liang’s labors are now abundant. Yet he is not completely liberated from the wilderness of his early years. Lu is almost forty years old, but doubt remains indelibly etched in his pieces. Between the contemporary and the traditional, he struggles to find artistic and personal liberation. Lu boldly embraces his dissatisfaction as his destiny and the fountainhead of his creativity, and he had already reaped great benefits from his personal quest for art as salvation.

Let us admire his fine achievements in this exhibition as well as the lonely road on which he travels. I believe his shunning of accolades and laurels is his own defiant expression of freedom.

自述與評論

一个古典主义者的都市寓言

李 旭

上海张江艺术馆馆长

认识陆亮,转眼已经十年了。

当年他还在中央美院读壁画系本科时,暑假回上海探亲,曾拿来素描和油画的习作照片给我

看,我当时只觉得他是个态度极其认真的学生,尽管创作还没有起步,但在同代人中造型基

础很好。他选择的不是那种聪明讨巧的风格,这跟他沉稳慎重的个性有关,中规中矩的古典

学院主义画法,产量很低,难度很高,想以此树立个人风格,着实需要坚忍不拔的定力。

十年之后再见陆亮,他已经在美院攻读硕士毕业,并留校执教,在导师陈文骥和曹力的影响

下,他的个人风格已经初步确立,2004年以来的一系列创作,令人眼前为之一亮。

陆亮的作品与市场上流行的古典风格明显地背道而驰,没有任何甜俗浮华的味道。他笔下的模

特儿几乎都是男性,又以生活中常见的进城务工农民形象居多,画面大都笼罩在凝重的深沉色

调里,内容都是当代人不甚熟识的中国传统寓言,充盈着哲学思辩的气息。从绘画语言上看,

陆亮直接得益于伦勃郎、卡拉瓦乔、拉图尔等西方古典大师,但他却用这样的语言讲述着极富

个人色彩的故事。在北京的长期生活,使他对当代都市的变迁经常抱持着怀疑和忧虑的心情,

城市规模的无限扩张,生态环境的污染破坏和历史记忆的切割断裂都令他在叹息中不断沉思,

一系列寓言、传说和梦幻题材的创作,以超现实主义手法表达了他对这些严肃议题的思考。

除却人物之外,陆亮作品的另外一个重要主题是风景。这些风景中没有白昼,只有黑夜、黎明

与黄昏,与那些人物画一样,所有景物都铺陈在各式各样的光源下:含混的太阳、晦暗的荧光

灯、令人惊异的闪电以及侵犯性很强的闪光灯……光,是陆亮作品中隐藏着的绝对主角,穿越

了空气和浮尘,弥合着明暗与色彩,所有景物,最终都以光的形式反映在我们的视网膜上。受

德国大师里希特的影响,国内许多利用摄影进行创作的画家往往在作品中强调“平、淡、虚”

的倾向,而陆亮颇为不同,为了精确描绘光线在不同景物上的微妙反映和大量质感细节,他往

往对作品进行一遍又一遍的往复操作,描绘、打磨、再描绘的过程会重复七、八遍,有时甚至

是十遍。故此,任何印刷品都不可能把这些作品的真实效果反映出来,对那些无缘得见原作的

观看者来说,这显然是一个很大的遗憾。可以说,陆亮是一位执著描绘光线的画家,他的名字

“亮”,正是“光”的意思,这也许并不是巧合。

在这个多媒体艺术形式充斥各种国际大展的时代,绘画已经开始悄然复归,在中国当代艺术圈

中,观念性绘画的势头也日渐旺盛。古典绘画技巧是否能够在这个时代重新焕发光彩?写实主

义的概念是否会在今天衍生出全新的含义?我相信,陆亮的持续努力一定会为我们呈现出一种

极具个人魅力的答案。

2007年11月15日

自说自画——笔记节选

陆 亮 中央美术学院造型基础部讲师

由阅读《庄子》引发的以现代人物场景来编织古代寓言的想法,并以古典写实手法作为表达的方式,引导我在2004年开始先后创作了庄子寓言系列,逐步确立了光线、叙述逻辑等个人基本的面貌,在技术与画面的控制上也不断积累着经验。《屠龟》是这批画中最后一幅,但记得当时颇不满意,因为从细致的程度上没有超过上一张。布、砖、沙发等在有前几张作品技术探索的基础上表达起来毫不困难。得来全不费功夫。但现在看来,此画确是那一批作品中创作思路最贯穿的一幅。沙发象征着王权,王者不见了,沙发上打开的书代表知识,有知识,才能成为统治者,反过来统治者也统治着知识的所有权与解释权。沙发是70年代的样子,那种红塑料皮的面料是我非常熟悉的。(小时候我家就有一个类似的沙发。)金色的布挂在沙发扶手上暗示着王的袍子,与翻开的书页都暗示着王的暂时离开。持丈者代表巫师、为王献策的人。献龟者渔夫余且,则是一脸媚相,是政令的实行者、无条件的拥护者。地上的瓦砾有工地上拣来的红砖与卵石,也有参杂其间一些秦砖汉瓦的残片,分别象征现代社会的激流勇进,与往昔文化的颓败。这也成为之后创作的一个母题。故事背景是现实生活中花家地一带的夜景。如戏剧舞台上的布景。龟是自然神,是最光亮的部分。代表不可能的存在与信仰—敬畏心的泯灭。

为了找气质相符的沙发,我骑车转遍了美院附近所有的小区,最后在花家地西里北区的老院中找到了沙发的天堂。各式各样,品类颇丰,性格不同。此沙发是最方正最有“官味”的。坐的地方都烂开膛了。它是在一堆老头打牌聚会的一个小角落里发现的。老头们也不太爱坐它,所以非常慷慨地“借”给了我。我很迂腐,答应要还他们的。但后来再去时,那一片地方已被围墙圈起来,开始平整土地,要建新的小区了。那些老头们也不知道又去哪儿聚了。那儿离南湖电影院很近很近。

很顺利地留校,但我很清楚自己的处境,不断努力创作已成了自己的生活习惯。毕业展的同时开始画《焚》。那是在找沙发时遇见的一次烧垃圾的场面,还是用我的小佳能不同的曝光拍好几张现场的照片,以表现火与阴影中东西不同层次,这层次有助于我的回想。正好有大小合适的画框,就大笔厚色铺开了。这张画从2005年夏天一直画到2007年秋天。靳先生来看过一次,说这火画得还不错,老先生虽然干瘦,讲起画来却是一兜子的劲。他提醒我用色上的问题,那大概是2006年年底左右的事。

开始不断有画廊、策展人、收藏家来看画,谈价、谈合作。开始卖画了,我觉遇上了一个疯狂的时代。这一切与你的艺术无关又很有关。泡沫无疑是存在的。大量的泡沫。好多重眼前时利的“艺术家”们以大生产的方式制造着艺术“商”品,把自己包装成明星以适应这艺术选秀的机制,艺术被娱乐化市场化了,各色人等都很活跃,我觉得自己象我的画风一样老旧、格格不入。我觉得好的作品应该是从内心里流出来的,是非常难得的。得有从容的状态,得花大量的脑力与精力,不该那么容易肤浅。不该仅仅只是想出个能成功或复制成功的“招”,然后不断复制、不断露面,我反感这一切。

好友梁硕从欧洲回来,我们一起在潭州吃饭。他的兴趣一直集中在空间与观念上,我问他有没有看到一些好的绘画作品,他说“维米尔!”想了一会“还有一个人,我一开始以为是摄影,凑近了看才发现是画的。和石冲、冷军那种细不一样,说不清楚,技术特高,画面也很平,几乎看不到笔触。但就是画的。”这此话对我印象挺深,我努力在想象中完形填空,构想着这种极单纯的感染力。我开始被强烈吸引:没有什么“观念”,仅是画照片,画一个有意思的难以舍怀的景物。开始制作《南湖电影院》。

这家影院原来是为南湖渠砖场职工盖的文娱场所。中央美院在1995年夏天突然迁临南湖渠,这影院是附近唯一一家文化娱乐设施。同学们发现丽都饭店的迪厅是后来的事了!进去看过几场电影,很便宜。后来北京全体院线都涨价了的时候,那儿依然很便宜。观众大多是民工,夹杂着我们几个学生。环境简陋,观众素质欠佳,退场时水泥地上厚厚的瓜子壳像一层地毯。

我在2005年留校任教后不久分到了一间半地下的小宿舍,使我又回到了阔别了五六年的电影院附近。上下班还常常会经过。那时的影院早已不放电影了。砖厂的旧房也都扒了,盖成了漂亮的小区,电影院像那个时代的破旧简陋的出版物,夹在时髦鲜亮的新书之间,不合时宜。照片是一次散步时,出于好奇,透过影院玻璃门朝里面张望时拍的,(画面右下角的黑影是门把手,老式那种)。里屋还亮着黄光好像有人住着,厅里的迎客松气势依然那么正,挺立着,看久了让人直想哭。墙角一排水池子应该是后来修的,它们似乎没有原先就存在的理由。水泥地是最老的那种,被反复踩踏得泛出油光光的微绿色,像玉一样润。后来在画里那也是我反反复复精心调校的地方。

翻出照片来画几乎是一时的冲动,但没想到彻底完成这张小画是半年以后的事了。开始时电影院还没拆,我画画停停,想着有空还可以再去看看。但再去时,那已是小山似的一座砖堆了!一辆工程车耷拉着机械臂疲劳地趴在那堆砖上。再不久那儿被清理平整,铺上草皮,插上几根牙签似的树苗,弄成了小区的花园。而我则只剩下照片来帮助回忆,画我印象里的老式日光灯,正气的枯笔迎客松,润如玉的老水泥地。

很多人用照片画得“平、淡、虚”,而我却努力把原来甚至有点“虚”的照片画“清楚”。我喜欢做完形填空。画面的氛围几乎第一遍就有了,画了两三遍就挺浓郁了。但我不满足。我要什么,我表述不清楚,只是不要能容易就达到的。我开始一遍一遍打磨,再画,再打磨。传说后羿练射箭先练看虫子,把虫子看得大如车轮就好射了。照片也可以。把虚的地方看清楚,复杂的地方看单纯。画笔越用越细。荷兰产的水性油画色让我把技法控制得很好!那张小画花在上面的时间很多,老婆都急了,认为我没必要为一张小品如此使劲。前后加起来,完整的投入在两个月以上,都够我完成一张二三米的大画了。

其实画面能让你使劲使得进去是一种幸福。画这样的画对我来说有如禅宗中那著名的公案:“随便找块转头磨成镜子。”我突然明白做人、作画,态度很重要。对象的选择、主题的明确只是随缘而定的,作为自由人,你最大的自由只是调整你的内心,调整做事的方式与态度。艺术有如人生。太多人急忙寻找自己的主题与形式,所谓的“招”,所谓的“占山为王”,好让别人记住他,在我看来只是追求“指月之指”罢了。

《南湖电影院》先后参加了2006ART北京,今日中国美术,与C5画廊的学院联展,反映都不错。好友王兵说,这是一张令人印象深刻过目难忘的作品。李旭说这张画有着一段影像的力量。孙景波老师在我画室看了一圈,说这张是最完整,最成立的一张。陈老师是最早见的:“就用照片画的?”他不置可否,但语气里的惊讶还是有以资鼓励的成分。“日光灯还可以画得再亮点!”他自己很深入的画过日光灯,应该有发言权。还是马老师直接。“别卖给那些傻大款,那些人也未必看得懂。你以后再也不会画出这样的画了!”这画在2007年10月初因为还房贷给买掉了,非常非常心痛,虽然是一个相知多年的好友收的。

《夜牧》我在基础部的仓库里发现了一付马骨架,很刺激的视觉感受。每根马骨上用毛笔严谨的标着骨的序号,象文物,该是老美院留下的遗物,我把它拉到素描课堂上,与模特摆在一起。有几个学生画面完成的还不错,但没有特别满意的,我想自己再画画。大约从06年3月初画到5月底,7、8月间又润色过两次。画得颇为顺利的一张,意图贯穿得也较完整。砖头与枯草是叫两个本科同学帮我搬上来的。模特的形象也是我想要的,一切都很顺利。不再是庄子寓言了,只是单纯的有关城市的寓言。碎砖依然是颠覆,暗示了现实中的建设与城市;枯草形似宋画,意指远逝的传统文化;马骨意指农耕文明的衰败。引路的老者消瘦精明,现实中人。破旧的汗衫、秋裤又有如梦境中,目光呆滞不知前途何方?后头的城市却在不断迫近、扩张。中间是旷野,暗色的玄冥之地。王兵说远处的背景太实了,前头的碎砖已足够结实,背景尽可黑得单纯空灵些!他提到在意大利所见卡拉瓦乔晚期几幅大作的背景处理,我觉得说得有理。没待我改动,画便买掉了。把想法留存到以后吧!我觉得此画的缺点是寓意太直白了,但这很难说,力量也在于这直白、生涩之间。王华祥来看,说写实的语言是可以做一些有意义的事情的,在这一点上我同意。

《煤库》延续《南湖电影院》之后的又一副室内小画。比起电影院少了好些人文的符号:迎客松等。或者说,电影院虽然简陋,它本身就是一个特殊年代的文化象征。在煤库,空旷的煤库,主题单纯得多,所指是对人类生存的焦虑。当我初次站在巨大的煤库中央,矮小的煤堆退缩在深处,煤块像宝石一样闪闪发光。煤库里冷冷地但蕴含着巨大的能量。象掉入了黑洞,怎么会那么熟悉又那么遥远!我决定开始画它。希望可以超过《电影院》。目前小幅已近完成,不过瘾,开了一张近三乘五米的大画。象个工程!要达到远观近察的“细”可能得画上整整一年的时间。既然开始了,我不在乎!我想自己一定是疯了!

《砖堆》构思源自弗里德里希冰山沉船一画。荒原上的废墟!现实中容易被轻易忽略的景象我试图将它定格成永恒,我利用照片和拣来的破砖一块一块在画室里死抠了好几个月。此画可能是在07年个展中展出效果最好的一幅。

《出走》2006年底,青峰意外发现怀孕了,我们觉得该顺其自然,准备结婚生子。那年她研究生毕业没留成校,也没找其他工作,生孩子也算是件事吧!好在我的工作稳定,卖画也略有收入,生活应该不成问题。但我觉得她不甘心。她和我都是那种表面上风平浪静,内心却总要和自己较劲的那种人。07年夏宝宝出生,全家充满了喜悦。小家伙出奇的安静省心,几乎没有妨碍我的工作进展,却占据了她全部的精力。她快乐而忙碌着,却又隐忍着,我感觉得到。在想象中我觉得她会在某一天不辞而别,象年少时听张楚扯着嗓子唱“离开离开离开你”的悲伤凄凉。现在的生活是否她想要的?有时候是,有时候不是。这张画的构思开始隐现:有阴暗的林子,象摆脱不了的梦魇;有羔羊,善良而顺从;有渴望独立的女人,火把代表她的意志。画面右下脚两个人物:执杖的老者象个疏忽了权力的牧人,稍年轻的或许是这个梦的编撰者“我”。

《追逝》源自《庄子﹒在宥》中云将、鸿蒙的故事。后来觉得高人不可见,便索性将逝者改为一袭空长衫,象是我们这代人和传统间的关系。画面似乎更有意味了!原来的故事背景“有宋之野,扶摇之枝”则被改换成我画室窗外的景色,因为那离一垃圾场很近,飘满了塑料袋,让人想起“限塑令”。

以上文字部分节选自我在2007年底出版的个人画册《夜游者》,加入了08年的两张新作《出走》和《追逝》。流水帐似的记录散乱而偏颇,纯是个人的角度。在此刊出希望能有助于对我作品和艺术态度的理解。因为单看画面往往会显得晦涩难懂。目前的创作基本可分人物寓意画和更为单纯直接些的景物画。我自己觉得后者更贴近我的内心。人物画里的问题更大一些,难一些。好的作品能将观众直接带进那氛围,而糟糕的画只会处处露着说教、拼凑的马脚。现在的我实在做得很不够!虽然画里的问题最终还是要靠自己解决,但高人的点拨常常是致关重要的,在此要深深感谢那些曾给我过帮助和指导的老师们、朋友们!

关于那条路

我只是寻找一种日常经验的视觉表达。

[城乡结合部的人生] 这条路要连通望京与来广营东路,期间会穿过五环,经过一个铁路的地道,经过原来的索家村,尽头是现在15号线的崔各庄站。 对这条路最早的印象大约是2004-05年间,梁硕从费家村香格里拉的工作室,搬到索家村更大的空间。他周末约我们去玩,大约是第一次走上这条路吧?从果岭往东钻过五环路下的桥洞就是另一个世界。城边村的世界。沿街密密麻麻的地摊,鞋帽衣袜,蔬果熟食,烟酒日杂--路人大多都是这都市的边缘人,在路两边的小饭店,洗头房、杂货铺里钻进钻出。冒着烟的煤炉子,满街乱窜的脏孩子,随意搭到街面来的雨篷等等,生动快活地活着,那么痛快,率直,满不在乎!摩的,小面,自行车,板车,摩托车,牲口车,大车小车都夹裹在一起沸反盈天,小心避让缓慢爬行,尤其那铁道桥,也就是之后描绘的“安全通道”,是个隘口,很少有顺畅的时候。 05年9月,梁硕申请下荷兰访学的机会,将索家村的工作室借我暂住。那时我好像刚刚留校。每天骑着自行车往返在这条路上,每天在感受着这喧闹的气氛。梁硕说他特别喜欢这种城乡结合氛围,充满活力与创造力,我深有同感。只是没有想到自己在将来会对这种生活的“遗迹”有哀婉叹息的心情,会花上这么多的时间与精力去描绘。 [亲历强拆] 在索家村住下来不久,某个早上醒来,突然发现院子里站满了警察,路口也拉着警戒线。很多看热闹的人群被拦在了院门外。偶尔沉闷的响动从南边传来,院子里还有零星几个刚起来还摸不着头脑的艺术家,都没法过去看究竟在发生什么!但那气氛诡异,听说是遇上了强拆,但拆谁家不清楚。我心里纳闷的是,怎么事先毫无征兆。 晚上从学校回来,去南边看,有几个学生在倒塌的断壁残垣间帮着尚扬老师往一辆车上抬东西。巨大的铁皮屋顶像坠落的机翼搭在碎砖堆上,整个南墙,变成了碎砖与瓦砾,玻璃窗也扭曲期间。可以想象机械臂粗暴的动作,弄碎了晨间的阳光。听说损坏了挂在墙上的尚老师的画。黑暗中学生在翻砖,摸索捡拾,而尚老师则神情木然,在车边站着。我上去打了个招呼,先生也无话。无论从作品到为人,尚老师都受到年青人的爱戴,享有威望,但或许正是这种爱戴与声望,才让先生遭受这无妄之灾的吧!后来的事态表明,人家冲着尚老师去似乎都是经过“设计”有意图的,而据说房东事先也是受到过警告的,但据说前几天还有人在交房租,照收,这是“维稳”的意图么?还是没料到真会动真格的呢?这是我第一次亲历强拆。我还清晰得记得那夜的色调,以及站那夜色中的尚大师神情。做艺术做到先生这样的份上也会遭遇如此的无奈,令人扼腕叹息。 但索家村的画室并未想象中的被迅速的拆平,不久之后那被毁坏的房子又被重新修整好,就像什么也没发生过一样,甚至一些搬离的艺术家又重新迁回来,但大约两三年后,那块地方,还是被抹平了,被抹得干干净净的。只是被延缓了,还是一出悲剧。 之后的几个月,我先是搬到学校的地下室,半年后(06年初)又从那儿搬到了燕郊。2008年1月又搬到黑桥,开始另一段噩梦,因为实在无法忍受哪儿的环境,09年底又从黑桥搬回望京。在高层住宅里画。到实在在家折腾不开时,再开始动脑筋找工作室,那是11年底。于是阔别了五六年之后,我又遭遇了这条路。 那时4星级的昆泰酒店已盖完,正等待开张。边上的高科产业园也已运转起来,摩托罗拉,爱立信就在其间。五环路边,总有一队队光鲜的白领和大巴班车,是气派干净的都市气息。而一出五环,景观顿时为之一变。原先热闹城中村的景象,全不见了。从路边的碎砖瓦砾间还可以依稀分辨出当年那些沿路小门面的墙基,水泥地或磁砖。原先最为热闹的铁路桥洞附近,也只剩下一幢红砖的二层小楼,大概是铁路局的吧!砖已退成了灰灰的暗黄色,让我想起前些年陈文骥老师画里的色调。小楼附近是几个巨大的土冢和一些颇有古意的杂树。两家洗车摊,就在近旁,红色的地毯已吃到了土里,边上露天放了一架洗衣机。只有那隧道是熟悉的,一点儿没变,还完全是原来的样子!而隧道两边原来密密匝匝的店铺摊位,以及熙熙攘攘人群和这车水马龙,沸反盈天的景象早已荡然无存。剩下的是一个被抹平了的北方的农村,一截真空,仅从路边的碎砖和地基上可以依稀辨认出原先的店铺,水泥地,磁砖地。原先站在道边村头或谁家庭院中的槐树榆树,枣树柿树,柳树杨树,还站在原来的位置,标志着一段过往生活的记忆。树龄都该在二三十年以上了吧,最大的大约四五十年?我猜。倒也没有特别老的树,那是建国后不久植下的,还是大跃进,生产队里种下的呢?那时的这庄子又是怎样的一幅光景呢?又是谁在这树下的纳凉唠嗑,吃着这落下的枣呢?而原先曾在这里生活过的人们现在又过着一种怎样的生活呢?会否念及这树底下的日子呢?当然极有可能的是,男人们挺着肚子开着豪车当着房东,双休日去就在附近的奥特莱斯SHOPING。早不在乎这失去的破村子,这村子存在的意义只是一种过渡,使劲造,使劲榨取,只是为了换回更好的未来。被弃是一种主动的选择,虽然11年的经济依然不景气,房价虽然还在高烧,地产商们却是谨慎拿地。附近的几个村子就这样被拆掉后弃荒在那里,有点像小时候在张乐平爷爷的漫画里看见的气息。 隔了些日子,当我再次经过这片荒原时,路的两边已砌起了一人高的围墙,只是用水泥抹上,并未粉刷,倒也齐整,肃静了。车在道上走,两边似乎是无尽的墙。而那荒原,我知道,就在那墙后面。 11年底工作室找停当了,在费家村。据说原本也是要拆的,因为高压线以及一座小型变电站的存在而得以暂时幸免。而在流传要拆之时,大批艺术家又搬离,如枝头的小鸟。我们那院的房东却和几个哥们集资盖了一片钢架结构的厂房,等着拆时的补偿,而听说不拆了。于是又有艺术家陆续再找回来,我就在这时进驻。那原是一间存放油漆的库房,被腾出来租给我,一百多平并不很大,好在离家近。房东的那个简易的厂房最终也被重新分割简单装修,出租给打工者,并起了一个略有乡愁的名字,“北漂公寓”。我一度非常担心消防的问题,因为在这联排的厂房里住着进百户人家,用电用火万一有闪失殃及池鱼,我就在隔壁,是首当其冲的!房东会舍得用好电线么?之后进去看过,一过道的灭火器,过道也比想像中的要宽,稍安,却也存疑至今,直等麻木了才好! 去这工作室的路有两条。一条是大路,京密路,偶尔会堵;另一条便是穿过原先索家村的这条近道。路面虽然并不平整,但似乎基本是畅通的。唯独这火车道下的涵洞,会车时会略显促狭,但基本上永远是畅通的。雨后也许会偶有积水弄脏车身,反正这车也开了有四、五年了,也不太爱惜了。我偏爱走这小道,也许是因为这路上的风景更合我的心境吧。尤其当我发现:路大约也是有生命的!路边的景致也一定是构成其生命的一部分,虽然有水泥墙。

[黄昏中的广告牌] 那广告牌是什么时候在那儿的呢?它躲在一排粗壮的行道树后头,原先上面还有打印的碧海蓝天棕榈树的风景照,写着“改善生产生活环境,实现崔各庄地区跨越式发展”,还有“相信政府,相信政策,支持腾退,和谐搬迁”若干时间之后可能是风把广告布给撕碎,又被扒光,露出白铁皮的板子。铅灰色的板子映着扭曲的光影,呈现出一种神秘变幻的色调,反而看不清它原来的本色。冷暖色带的抽象变化让人想起深海底部正在捕食的乌贼用来迷惑对手时脸上会呈现的催眠作用的虹彩。

我有时也会实在按捺不住想重看一眼那荒原的好奇,停下车,从这墙边留着的路进去。从2011年至今,这片土地倒是好像没有太多变化。我甚至能依靠地面上仅存的痕迹印证着回忆,找出当年那个艺术家大院儿。进门的路,一家家的院子,水泥或是瓷砖地面,以及沿着院墙还挺拔着的杨树。一次看见有几辆拖拉机停在那儿,男人女人们在剔旧砖,大约是没有人管,见我过去,还有些紧张。是否因为见我手上拿着一架单反相机。我忙跟他们解释,我只是个画画的,来闲逛,顺便拍点照片当素材,没用的。他们是否在做违法的事呢?不得而知,只是从神情上看,象。中国人似乎最怕惹麻烦,以至行为苟且,总是一脸谦卑。 今天沿着墙角多了一摊烂菜叶,明天多了一堆建筑垃圾,其中会有个摔破了的坐便器,要不就是某块缺了角的大理石块滚到了路边,开车得小心地避让。这路似乎会生长,长出的是漫不经心与漠然,丑陋的中国人的心态。

不知何时起,有些清运渣土的大车会开进这条路,应是要去那荒野里倾倒。路面开始是小块零星的土疙瘩,形成搓板路。之后,大块的遗撒在墙脚连缀成起伏的丘,在夜晚的车灯下连绵起伏,颇有些宋画中披麻皴的意味。有几处路面在巨力的碾压中褶皱,开裂了,破碎成坑,顺辙为带,脆弱得如同压碎一块饼干,这些碎裂或许在某个司机们辛勤操劳的夜晚彻底开了花。以至对我这种抱有探索乐趣的驾驶者来说突然在某个早上发现,基本不用尝试了,直接掉头回去! 之后也会被好奇心驱使,几次到这桥洞附近。或是因为雨后水太深,或是因为被车河堵死。也有几次冒险在村里探路穿行。东辛店和北皋已经连成了一片巨大的城边村,各种简易搭建的房子和我所住的所谓“高尚小区”和这儿仅隔着一条五环路,有一条小河贯通其间。走这村子让我总算明白了为什么那条河那么臭。在那村子里的河道上,什么东西都有!让我想起《千与千寻》里小千给帮忙洗澡的“妖怪”河神。还有之前住过的黑桥。可能北京周边的村子大约都是这景象吧!这想法让我不寒而栗。对这些外乡人而言,这只是一个落脚点,人生的一个中转站!并非家园,他们来此抱着某种目的,似乎也只可能在此实现,但在这过程里受到的冷遇或歧视,欺负或怨气,都化成了这么一种漫不经心肆意随性的行为当中。焚烧,或者是乱丢垃圾,这些在村里是常态。正是这种冷漠和漫不经心将这世界拖下地狱的吧! 我觉得我生活在两个世界,一个是学校和家的世界,努力与世界接轨成一样的现代细腻光鲜,而另一个是工作室周围的世界,混乱粗糙肮脏,让人焦虑。但是,这两个世界真那么截然分明?难道没有交融混杂的部分么?在这现代光鲜的背后是否也有着那种漫不经心的粗陋混乱呢?抑或在这混乱与肮脏的环境里也会有着理性的反思而积极的人生体验呢?

[安全通道]

有一段家里订着新京报,我偏爱翻那些意外事故的新闻。什么某位白领还是个tl,掉到一个冒着热气的水坑里,烫死了;某位盘踞路中央的钉子户,突然被带走了,两天之后,路面修的乌黑锃亮,似乎什么都没发生过;然后是某幢在建的十几层的居民楼突然倒了,但大家都惊叹乃至赞美那些几乎还完好无损的窗户。比起来桥洞底下变泳池,以至汽车驶入打不开车门,活活将人闷死,也并不那么稀奇了吧!7月21日大雨那晚因为接送朋友正好在路上。走的北四环,虽然几乎都是倾倒式的暴雨,也照样有些堵,但还是安全回家了。 我决定画这桥洞,想要表达一种吸纳的力量。用夸张的透视,地下斑驳的水渍,天顶上被蹭出来的一条条亮道,那都是些违章超限的车被硬拽过去时留下的,还有路边上随意挂着的电线。而远处城市就在那里闪烁隐现,你可能在这儿出了状况,也可能硬挤过去,安全通过了。“7.21”事件之后不久,桥楣上用红漆写上了“雨后水深,注意安全”,几个粗糙的大字。 又是雨季,即使桥洞积水尚能过车,那条开花的路也会将车溅得惨不忍睹吧。虽然出于懒惰或者环保的理由,我洗车很不勤,但也不想总是将车弄得过份脏,所以有一段时间只是怀念着那条可以开越野赛的路。是否平整一些了呢?尤其在京密路上遭遇了几次堵车之后,总有些后悔,如果换那条道,说不定早已坐在工作室的椅子上喝咖啡了呢!虽然会把车子弄脏。 那条路,应该也分担了不少车流吧,就这么瘫痪在那儿,会到何时呢?要修一下应该会很贵吧,但我们每年交这么多养路费,不是就应该拿出来干这个事的么。就这样大约有两个多月的时间吧,我常常还会想起那条路,只是不太有重走的勇气。 直到某次实在按捺不住好奇,再次走去,竟然有几个工人在桥洞边挖下水道。我有些好奇,似乎“上面”要下决心彻底治理了。但我多少些怀疑。底下有连排水道么?还是仅仅只用北方所说的“阴井”靠自己往下渗呢?还有,如果下面挖有下水道的话,一是排水口的大小,是否来得及排水;二是北方雨水中泥沙量大,有一两次大雨就该将下水道的口给淤塞了吧!但看他们施工的机械以及排场,似乎真有心去此顽疾似的!而事实是,经过几场雨,这地道还会有着十来公分的积水。不太深也并不畅。再之后,那井盖被人取走,一个矩形的黑洞口就这么敞着,车与行人都得小心避绕!再有一段时日黑洞被填得浅浅可以见底,但还是这么敞着,真不知有人不小心踩进去过没有,崴过脚没有! 那路,给整个刨平了一层,被反复填以建筑垃圾的部分被彻底铲平,我以为他们又会只修补一部分,之后几天略做停顿后,见整条路都被铲了一遍,一切的坎,沟,洞,路边的垃圾堆,都被清运到了哪儿?荡然无存,干干净净。再几天之后,一条黑的发亮,象黑芝麻糖似的一条新的路,象一条国外的路,那种深色在苍茫的北方显得份外扎眼,即使夜晚用车灯打出来的光,也会被它全部吸收掉。夜的色调也因这路面而完全变化了。我心里苦笑,但车胎在这么平整有感的路上走,很爽!我又满不在乎地快乐起来。 的确,满不在乎的快乐确是种“智慧”的反应,没几天后,先是从路口往里延伸出苍白清晰的车道,再几个月后这条新路也渐蒙上了土,日渐苍白。而路两旁的土堆,垃圾堆,又渐再次出现,时至今日,早已连缀成片,不时会延伸侵占到路面上,但不管怎样,这路比原先总是好走了。

地標:被陸亮照亮的生活角落

宋曉霞

北京,連續幾天的霧霾。無論內城的「十大建築」,還是東三環的CCTV大樓或北四環的盤古大廈,這些北京的新舊地標都沒入霧霾不見了。有人在網上打趣說這裡是仙境,可是關於PM2.5的各種分析,卻讓人焦慮、不安、無助,而且得半憋著點氣,不敢深呼吸。這種無所不在、難以名狀的刺激,給人無可遁逃的絕望感。霧霾裡頭有人、有城、有呼吸、有猝亡,有一種持續的高度的精神緊張。陸亮的作品,就在最平常的景觀裡內蘊著這樣一種精神緊張,他稱之為「當代的中國社會氣質」。

夜晚的廢墟、爛磚堆、焚燒著的垃圾場、空寂的舊影院、運空了的煤庫、隔離的病區、陰森森的地洞、夜路上的柳樹、暴雨後積水退卻的通道、黃昏中的空廣告鐵板……陸亮的畫面正在逐漸地清除人物的形象,也清除著敘事的痕跡。留在畫面上的是晦暗、陰霾、暗夜的場景,被燈光照亮的水泥地、渣土地和泥濘的車轍成為畫面的焦點,猛然地抓住了我們。陸亮說:「將日常的東西突然抽離出來,跟它周圍環境割裂開,給它一束光,它一下就有了自己的意義。」日常生活留在我們心底的許多微小的「裂縫」,霎時被驚醒。

陸亮與現實的關係是感受性的。比如在他決定畫柳樹之前,他花了兩年的時間等待這片落著土的柳葉,突破霧霾般的現實世界和迷惘的記憶世界以及重重歷史文化世界重新找到自己。當年彌漫在工作室的垃圾場怪味和隔壁翻製雕塑的玻璃鋼味兒,也隨之穿越而來。在急遽變化的生活中,陸亮卻刻意地讓自己從容地感知這個世界。他讀書,關注時事,卻不用概念或利益決定自己畫什麼的問題。陸亮的作品不是理解性分析的結果,而是他直接面對現實的體驗,是從他自己的切身感受裡拿出來的東西。經他挖掘過的日常生活角落,可以直接切入我們時代的肌體。

陸亮偏愛暗夜豐富的色彩,他遊蕩在夜晚,從朦朧曖昧的光線中獲得的靈感是什麼?暗夜裡仿佛有雙「無形的巨手」,《磚堆》讓什麼分解撕裂?《焚》又讓什麼灰飛煙滅?《煤庫》是陸亮里程碑式的作品,能源、生存、環境保護這些概念遠不如浸滲在畫面每一處的不安那麼令人驚悸。這件作品,讓人領教了陸亮在平靜地徐徐道來中的驚心動魄。倘若《南湖電影院》是對自己所從出的往日社會深情的驚鴻一瞥,《夜路-安全通道》就是對自己平常所在的今日社會的驚悚描述。關於《夜路-柳樹》,畫家自述:「這是一條令人壓抑迷惘的夜路,盡頭的黑暗叫人窒息,有如夢中孤立無助恰又危機四伏。」這些夜晚的氛圍,深深紮根於我們生活於其中的現實。就陸亮而言,夜景的描繪比直接的人物描繪更能讓人感知這個時代。

從全球的視野來看,陸亮的藝術在今天都很各色,他有自己的主見和性格,也有獨特的格調、格局和風格。當代藝術與社會的互動已漸成主流,陸亮想畫出「時代的肖像」,在當代中國拿出一個藝術家存在的態度也不稀奇。陸亮的獨到之處在於,他要把自己的宏願落實到繪畫上,落實到具體視覺的感知上。不必說歐洲畫家以古典油畫呈現自己的「真實」以及對世界的理解已有漫長的歷史,也不必說百餘年來寫實油畫引入中國的幾代變遷,單是現在古今中西的糾結、寫實繪畫市場的誘惑就有無數的陷阱。陸亮用的是笨辦法,自己跟自己較勁,幾年前就聽他說:「畫面能讓你使勁使得進去是一種幸福。」

當代藝術呈現非視覺化的方向,而陸亮卻逆流而上,要在繪畫「做」進去,通過反覆的「折騰」,把那些我們在照片中看不到的、隱藏在圖像中的微妙感覺、瑣碎感受都表達出來。他像農夫耕田一樣,將畫面上的圖像重新挖掘了一遍,用陸亮的方式建立圖像與情感之間的「連結」。比如《南湖電影院》,他在畫裡反反覆覆精心調校過的水泥地,畫出了老式的水泥地被反覆踩踏得泛出油光光的微綠色,像玉一樣潤的色調和質感,「連結」了我們對即將消逝的生活的複雜情懷。《夜路-安全通道》裡的諸多圖像細節,無論是道頂上長長的劃痕、地面泥濘的車轍,還是兩側或許在積水裡泡過的電線,以及遠處閃爍著幾點魅影的樓群,這些或模糊或清晰的圖像經過陸亮的提煉,都強力「連結」著我們每個人的惶恐與不定。《夜路-柳樹》的葉子上都是灰,因為旁邊就是工地吧,地上的石子兒和土疙瘩「連結」著環境的近憂遠慮。陸亮畫的柳葉似乎也是乾燥發炎的,像上了火的嘴角,一動就痛。

雖然陸亮畫的不過是日常生活的角落,其《磚堆》的構思卻源自弗里德里希(Casper David Friedrich)的冰山沉船。他的作品常常像古詩用典一樣引入西方古典繪畫的語言,有意思的是,他從林布蘭(Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn)、維梅爾(Johannes Vermeer)、馬奈(Édouard Manet)、戈雅(Francisco Goya)的寫實語言裡,卻體味出謎一樣的不可知的力量。那些經典的視覺經驗,在當代繪畫的語境中融入了陸亮體認世界的方式,他在介入當代中國的同時,也創造性地延續了經典。

《虎跑夢泉》是與中國古代經典的大膽對話。在用油畫結構的各個形色空間中,是光斑閃爍的結實又虛幻的山石,為了讓山石蘊含更多的動勢,也更加潮濕堅硬,陸亮在色層上追求年代久遠的壁畫那般輕盈,而筆觸則嚮往范寬、黃賓虹一樣豐富密實。《煤庫》中煤堆的形態以及畫面上的用筆,似乎也在尋找董源、米芾、米友仁、高克恭的山水形態和皴法;《夜路—柳樹》中的柳樹的姿態,不僅讓人想起「昔我往矣,楊柳依依」的詩情,也有宋代山水中留下來的經典語言形態。當然這一切陸亮都是在西式構圖中,以隱晦的方式追求的,他把古典形式可靠密實地種植在自己的土地上。

在這樣一種越來越慢的畫法中,一幅畫也許需要兩三個月,或許需要好幾年才能完成。有人說,全世界再也沒像中國今天如此複雜荒誕的環境。在陸亮的畫中,不是現實被表現得深刻,而是他感受得深刻。面對他的畫,你似乎都能聽見歎息的聲音。陸亮創造了一種全新的當代景觀:日常生活的角落,卻蘊含著驚心動魄的精神張力;在無聲的畫面中,有許多強烈的念頭與衝動在暗中湧動;既帶有入乎其裡的體溫,也有出乎其外的審視與質疑。

陸亮是我們時代的抒情詩人,他的作品才是我們這個時代真正的地標。

不得意也可以成為一種能量—解析陸亮的繪畫行為

陳文驥

有人因作畫而得意,有人因不得意而作畫。

一些藝術家可能因為成長過程有某些特殊的經歷或者缺乏某種環境的營養,成人後社會化程度不夠理想。在多次碰壁後仍然無所適從,心理上或多或少地會有一些向內的收縮。行事時也格外的謹慎,長期的謹慎會使神經過度的敏感。而因敏感,也造成內心反應更為細膩。具備這些品質的人,面對藝術的態度時常惶恐而謙卑,歪打正著的具備了某種藝術家特殊的品質。這類藝術家我稱之為不得意的作畫者。我猜想陸亮應該屬於因不得意而作畫的那種人吧。根據是我站在他的作品前總能嗅到一絲自省的壓抑氣息。他的作畫過程不順暢,有著太多的糾結,經常在即將完成階段又做很大的改動。儘管他在開始準備階段已經非常投入了。每次他還是要改來改去。這使他的作品很耐看,把他的作品放到一起看,沒有批量生產的油滑。

從旁人看來,他一直順風順水:九十年代進入中央美術學院,本科生,研究生,留校任教。學習期間素描作業還獲得過學院年度獎勵,屬於那種品學兼優的好學生。表面上他與當時的七零後的同代人沒有什麼不同。

使他沒有得到預期的安逸原因還是來自他內心原始的不得意。在學生時代他就對當代藝術思潮非常關注,對學院的傳統教學體系懷疑和猶豫。也曾在暗地裡試驗了各種可能的風格和材料,很長時間沒有找到明朗的方向。陸亮確立現在的寫實畫風應該在十年前,即將步入而立之年的他通過幾幅素描和油畫習作,逐漸地明確了自己的藝術表述立場,一種具有新古典精神的寫實繪畫風格成為了他的選擇。令人驚訝的是他選擇了和他的同代人逆方向的不歸之路;自甘邊緣化。看上去這個選擇有點悲壯。

進入寫實表達系統,憑藉他扎實的寫生功底,順著前人走過的車轍,應該是很快能從市場中獲得實惠。他卻獨獨對不那麼討好人的題材和苦澀費解的視覺角度情有獨鍾。他以一種「澀審美」立場來強調自己的藝術取向,無論在藝術的態度上和美學的標準上他都在自我較勁。畫面中每一道艱澀的筆痕都透露出他的作畫程式始終處在反覆無常的糾結中。我們看到更多的是他對事物無法輕易確認的困惑。醞釀於內心成就了他的藝術品質。初期的寓言性題材繪就了一幅幅令人費解的視覺文本。那些孤寂絕望的落日,夜色裡的突然亮起的篝火,讓觀眾內心有股莫名的不安。近幾年他開始熱衷於對現實場景的描述,貌似豪無情感的畫面下,隱約透露出莫名的感傷和無助,時間被凝固。打破了大眾的欣賞習慣後又重新建構一種專屬於他的新的美感體驗。

如今他不那麼取巧的表現方式成就了他的作品中的一種可貴的氣質。他說過:「畫面能讓人使勁使得進去是一種幸福。」甚至到了今天,他的繪畫事業應該說成就豐厚,我仍然感到他沒有從原始的惶恐中徹底解脫。已近不惑之年的他,依然有著太多的困惑反映在他的創作中。在這被當代和傳統藝術的雙重勢力擠壓下的有限空間裡,他努力尋求自在,尋求解脫和對生命的體驗。他接受了不得意是一種生來俱有的命定,已經成為他創作能量的來源。他在借助繪畫救贖自己,而且從中獲益。

讓我們通過觀看他的個展來檢驗他今天的成就。在這次展覽中我們仍將看到他默默行走的身影,避開那些光環和歡呼,我相信這是他主動的選擇。

Künstlerprofil

陆亮,1975年生于上海,先后就读于中国美术学院附中,中央美术学院壁画系。2005年硕士毕业,留校任教。现为油画系教授,硕士生导师。

个展

2017 「记忆场-陆亮个展」,诚品画廊,台北

2014 「夜路-陆亮个展」,诚品画廊,台北

2007 「夜游者」,苏河艺术,北京

群展

2021「成都双年展」 ,成都市当代艺术馆,四川,成都

「系谱-写实油画教学研究展」,中央美術學院山东艺术教育中心,信尚美术馆,济南,山东

2019「呼吸-中央美術學院造型学院青年教师提名展」,大都艺术空间,北京,中國

2018「具象散居」,纽约艺术学院,美国

「意义的回归-中央美術學院油画系教师进行时」,中央美術學院美術館,北京

「师严道尊-中央美術學院油画系第三工作室教学研究展」,中央美術學院美術館,北京

2015「接力-中央美术学院教师写生创作展」,中國美術館,北京

「历史的温度:中央美术学院与中国具象绘画」

2014 「選擇-中央美術學院造型學院提名展」,中央美術學院美術館,北京

「超级景观-图像世界的多重逻辑」,石家庄美術館

2013 「來自北京」,紐約藝術學院,紐約

「學院-中央美術學院青年教師十人展」,今日美術館

「CAFA 教師-中央美術學院教師創作特展 2013」,中央美術學院美術館,

2012 「在當代- 2012 中國油畫雙年展」,中國美術館

2011 「十年-中央美術學院造型學院基礎部教師作品展」,中央美術學院美術館

「學院-中央美術學院青年教師八人展」,百雅軒,北京 798

「東方既白-中國國家畫院建院 30 周年院慶展」,中國國家畫院美術館

「第四屆全國青年美展」,中國美術館

2010 「造型-中央美術學院造型學院教師作品展」,中央美術學院美術館

「油畫藝術與當代社會-中國油畫展」,中國美術館

2008 「第三屆北京國際美術雙年展」,中國美術館

2007 「融合與創造」,首都博物館

2006 「今日中國美術大展」,中國美術館

2004 「上海青年美展」,劉海粟美術館,上海,中國

「第十屆全國美展」,廣州美術館,廣州,中國

獲獎

2005 中央美術學院畢業展一等獎

王嘉廉油畫獎學金一等獎 1999 中央美院畢業生作品展一等獎

LU Liang

1975

Born in Shanghai, China

1999

B.A., Department of Murals, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China

2005

M.A., Department of Murals, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China

Present Teaching at the Central Academy of Fine Arts

Solo Exhibition

2014

Night Road, ESLITE GALLERY, Taipei, Taiwan

2007

Night Wanderer, CREEK ART, Beijing, China

2003

Fabricated Space, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China

1998

All About Xiao Jing’s Living, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China

Group Exhibition

2021

Chengdu Biennale, Chengdu Museum of Contemporary Art, Chengdu, Sichuan

Genealogy - Realistic Oil Painting Teaching and Research Exhibition, Shandong Art Education Center,CAFA ,Jinan, Shandong

2019

Breathe-Nomination Exhibition for Young Teachers of the School of Plastic Arts, CAFA, Dadu Art Space, Beijing, China

2018

Figurtive Diaspora, New York Academy of Art, United States

The Return of Meaning - In Progress by Teachers of the Oil Painting Department of CAFA, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing

Teaching and Research Exhibition in 3rd Studio of the Oil Painting Department of CAFA, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing

2015

Relay - Sketching Exhibition of Teachers from CAFA, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

The Temperature of History: CAFA and Chinese Representational Painting

2014

Choosing: Central Academy of Fine Arts Annual Fine Arts Nomination Exhibition, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing, China

2013

From Beijing, New York Academy of Art, New York, USA

Academy: Exhibition of Works of 10 Young Teachers from Central Academy of Fine Arts, Today Art Museum, Beijing, China

Teachers’ Work of Central Academy of Fine Arts 2013, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing, China

2012

IN TIME: 2012 Chinese Oil Painting Biennale, National Art Museum, Beijing, China

Art Classics: China National Academy of Painting Exhibition, Sunshine Art Museum, Beijing, China

Progress Every Day: Works of Masters-Nominated Exhibition, Zhouzhong Art Museum, Beijing, China

Not Only Paper, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing, China

2011

Foundation .10 years, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing, China

Academy: Exhibition of Works of 8 Young Teachers from Central Academy of Fine Arts, Baiyaxuan 798, Beijing, China

The 4th National Fine Arts Exhibition for Young Artists, National Art Museum, Beijing, China

2010

Works by Teachers at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, CAFA Museum, Beijing, China

Oil Painting and Contemporary Society: Chinese Oil Painting Exhibition, National Art Museum, Beijing, China

The Power from Academy: China Central Academy of Fine Arts Contemporary Art Exhibition, Times Museum, Guangzhou, China

2009

60 Years of Drawing: Central Academy of Fine Arts, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing, China

2008

3rd Beijing International Art Biennale, National Art Museum, Beijing, China

Future Sky: Chinese Contemporary Young Artists Works Selection Exhibition, Today Art Museum, Beijing, China

National Exhibition on Painting from Nature, National Art Museum, Beijing, China

Convergent Paths: A Joint Exhibition by China Central Academy of Fine Arts Professors, Chan-Liu Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

2007

Fusion and Creation, Capital Museum, Beijing, China

The 1st Painting from Natural Biennial, Art Museum of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Guangzhou, China

Academy Exhibition Series - Central Academy of Fine Arts, C5 Art Centre, Beijing, China

2006

Grand Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art, National Art Museum, Beijing, China

2005

The Displacement of Face, Aurora Gallery, Beijing, China

Colleagues, Convergent Paths: A Joint Exhibition by China Central Academy of Fine Arts, The Exhibition Hall of CAFA,

Beijing, China

2004

Shanghai Youth Art Exhibition, Liu Haisu Art Museum, Shanghai, China

The 10th National Art Exhibition, Guangzhou Art Museum, Guangzhou, China

Award

2005

Excellent Award of the Central Academy of Fine Arts Graduation Exhibition

First Prize of Wang Jialian Oil Painting Scholarship

1999

First Prize of the Central Academy of Fine Arts Graduation Exhibition